- Home

- Caroline Wood

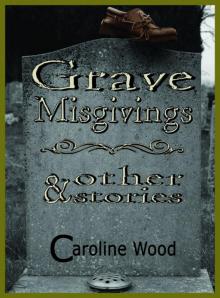

Grave Misgivings

Grave Misgivings Read online

Grave Misgivings

Caroline Wood

Smashwords Edition

Copyright 2013 Caroline Wood

Smashwords Edition, License Notes

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Table of Contents

* Fixed Expression

*Clean

* Foothold

* Growing Things

* Wings

* The Cobbler

* Resident Power

* Shaggy Dog Story

* Ducks

* The Collection

* Menu

* Unattached

* Suspicious Nature

* Touchy Feely

* Things To Do

* Home from Home

* The Last Train Home

* Grave Misgivings

About the Author

* Fixed Expression *

I’ve sat here for three quarters of an hour, trying to look all concerned and understanding ready for when he opens his eyes. I’ve been out and come back twice. That filthy muck they call coffee clutched in one hand and a gorgeous bouquet of flowers in the other. But does he rouse himself? Does he bugger. I’m a patient man, and fair do’s, he’s been through it with this surgery, but let’s not forget who’ll be settling the bill. So I decide its time for a look. I shake him a few times but nothing doing, so I dig my fingernail in his wrist. Just enough so he can feel it through the anaesthetic.

Flat on his back, he looked like an Egyptian mummy. Now they’ve propped him up on his pillows, he reminds me of the Invisible Man. I can’t help laughing – the image of him as a pair of black-rimmed specs floating along beside me really makes me chuckle.

Trust him not to go along with a bit of fun though. He puts his hands up to the bandages and starts making this wailing noise. Not a nod in my direction. He doesn’t even thank me for the flowers. We’ll have none of that, I tell him. You’ll get your stitches soggy. He’s all teeth and eyes, and they’ve left the top of his head unwrapped, otherwise it’s crepe bandage right down to the collar of his silk pyjamas. I ruffle his hair, which could do with a wash, and tell him not to upset himself.

What have I done, what have I done, he keeps moaning. So I tell him. Listen, Popsicle, I say, what you’ve done is to spend a couple of nights in the best private clinic money can buy. You’ve had nurses and porters waiting on you hand and foot; you’ve been surrounded by more flowers than the crematorium at peak season, and you’ve had me holding vigil day and night at your bedside. What you’ve done amounts to living in the lap of luxury. If anyone’s done anything worth mentioning round here, it’s yours truly. I’ve had my hand so deep in my pocket, there’s nothing left but fluff. And the stress I’ve suffered getting you through this has wrecked me.

That shuts him up. All I can hear is a bit of muffled sniffing. He reaches out and takes hold of my hand. It gives me a bit of a shudder to be honest but I let him cling to me. Just for a while. It’s an improvement on having to see his face, but those bandages didn’t do much for me either. I make myself think of the future, that’s what has always kept me going with this one. He’s got potential. I could see it from the start.

I ring for the nurse and ask if we can have a bit of a peep. Virtually spat at me, she does, saying it’s far too soon. Wants to watch herself, I think. Not a good idea being rude to the people who pay her wages. I catch a glimpse of her thick ankles.

I decide to wait for the next shift to come on and have a word with that nice Jason. He’s got a pleasant word for everyone, and a lovely way with a bedpan. Meanwhile Boris Karloff needs a pep talk to cheer him up. He’s got a bit of a nerve if you ask me. Not many people get the opportunity to make something of themselves like this. Most of us are stuck with what we’ve been born with. Of course, in my case, that’s been a blessing. But lover boy needed a bit of help with what nature had dished out to him. Not that he was ugly. Let’s just say there was plenty of room for improvement. We tried the clothes and hairstyle approach. It helped, but there’s only so far you can go with all that. I’d got to the stage where I was ordering two of everything. Once we’d got him down to my size, that is. He looked like me, walked like me, smelled like me. We turned a few heads in the clubs, I can tell you.

In the right light, and if he wore dark glasses, the effect was brilliant. The trouble with that though was the shock when I got him home and it was just plain old Gary with his hair done the same as mine. He’d look like a dog trying to please its master, and wait for me to praise him. And I did in the beginning. As time went on though, I got sick of the sight of him. I could hardly bear to look at his stupid grinning face as he searched for my approval. We got round that one for a while by playing about with a bit of bondage and dressing up, with him in the masks, obviously. He’s always been willing to go along with whatever I want, but then he’s in no hurry to return to the life he had before I spotted him. I tell him all the time; he’d be nothing without me.

It got worse, the problem with his face. I couldn’t even pretend with the mask in the end. I started to hate him for looking the way he did. I avoided his face; just catching a glimpse could make me furious. There I was, spending a fortune on beautiful shirts and trousers you wouldn’t believe. I was having him manicured and coifed by the best people. He was in top condition. But none of that solved the problem of his face. Every time I looked at him, my stomach turned. It dawned on me that I was going to have to do something or he would have to go.

I was reluctant to lose him because we’d got a good routine going. There’d been a string of boys before him, and the trouble I’ve had with some of them would make milk curdle. But I couldn’t close my eyes to this problem. So I put it to him. Popsicle, I said, either we get your features rearranged, or it’s back to the dole queue and that poky old flat for you. It took some persuading, but I knew he’d come round. He likes the finer things in life, now he’s had a taster.

He’s in his element in the world of semi-professional showbiz. I know he’s set his sights on the big time theatre, but he’s not too averse to the type of entertainment provided by six foot queens with their dicks strapped down under sequinned gowns. Buggers can’t be choosers, I tell him.

Anyway, he agreed. What’s a few nips and tucks these days, I said to him, with my eyes fixed firmly on his medallion. I played it down for his sake, but the cost of it took my breath away. They’ve got you over a barrel, these clinics. They see the furs and handmade shoes and that’s it, they charge what they like. Then there’s the celebrity bit – they know I’ll want this all kept private, so they bump up the charges for doing it in their state-of-the-art hospital that looks like a secluded country mansion. Hush money, I call it. Still, for the right price, they’ve got a chap here who will do exactly what you want him to, no questions asked. Top man in his field – he’s got clinics like this in all the big cities. And he’s his own best advert – there’s more hair on his head now than when I met him, seven years ago. I knew I was making a wise investment by letting him get to work on Gary’s face.

I gave him photographs of what I wanted. Had them professionally done. Every angle you could imagine. The big man said they would help him while he performed his surgery. We laughed when I said if Gary didn’t come out looking like the pictures, I’d be sending him back. He thought I was joking.

Well, it looks like I won’t need to send him back

anyway. Jason gives me a sneak preview. He’s much more accommodating than that dragon with the ankles. I shake with excitement as he unwraps the bandages. Gary is still drowsy and droning on about the pain and how he’ll never be the same again. That’s the general idea, I say, and nudge Jason’s pristine white tunic. He gives me a smile and tells me to be prepared for some swelling. Then he gently lifts the final coil of crepe.

Even with the bruising and stitches, I can see it’s a wonderful piece of work. I will never have to look at Gary’s face again. My suffering is over. Tears well up in my eyes as I look at the vision in front of me. I stroke Gary’s arm and tell him through my sobbing how pleased I am. Popsicle, I say, the man who did this is an artist. Just wait till you see it. That sets him off and it’s back to the wailing all over again, so I leave Jason to sort him out.

Three months on from the op and Gary still won’t look in a mirror. Not that he needs to, but I can’t understand his lack of curiosity. It’s natural, isn’t it – you get something new and the first thing you do is try it on and see how it looks. I get annoyed with him, remind him how much money it all cost, but he doesn’t say much these days. Contentment I suppose. He’s got a wardrobe full of designer clothes, two cars, the swimming pool, the snooker-room, luxury holidays all over the place, and all the glamour of living with me. He’s still willing to please me, wears what I tell him to. We had the white suits on last night, for the opening of a new club. Lots of shimmer and dazzle. Popsicle, I say, when he does a twirl for me, you look absolutely stunning. He looks straight at me. You mean I look like you, he says. Exactly, I say, and watch my dimple stud his chin as we both smile our best smile

* Clean *

I knew they were twins. Everyone did, obviously. But even though they were identical, there was something different about them. It was almost as if there was a main one, and the other one was some sort of copy, a weaker version of her sister. I felt sorry for the carbon-copy sister, which was a predictable response, I suppose – sympathy for the underdog and all that. Only she wasn’t really the underdog. Rose Savage wasn’t under anything. Not that her sister wasn’t as dominant as she seemed. Keeley definitely called the tune. It’s just that Rose turned out to be stronger than anyone thought.

My first encounter was a few days after I moved into the flat. There had been no sign of them while I was moving my stuff in. I thought perhaps they were away – before I even knew who they were, of course, or how it would change my life once I did. After I’d slept in the new place three or four nights, and was getting used to all that space echoing around me after the bed-sit years, I caught my first sight.

Two brown coats, big buttons down the middles, and two head-scarves, one pale blue and one deep lavender. They were scurrying up the front path. That was all I saw. They moved along quickly, to their entrance at the side, and I had no time to go out and say hello.

The flats look like houses. I was so pleased to be offered mine. It had been empty for ages, but the man at the council never mentioned that. He gave me the key to have a look round and I remember thinking there had been a mistake because I wasn’t entitled to a house on my own. Then I saw the two paths and noticed curtains in the upstairs windows. That’s the only way you can tell, really. All the windows have mis-matched curtains upstairs and down. Sometimes there’s a real clash of tastes, with plain, neat nets on the lower floor, then frilly, flouncing ones above. In the cul-de-sac, you get either an upstairs or a downstairs flat, and half a garden at the back and front.

They are old, solid buildings with large rooms and black lino-tiled floors. There’s no heating except for an open fire in the sitting room. It was cold and musty but I didn’t mind. I tried to spread my things around to make it cosy. It was very quiet in my flat. No sound at all from the twins upstairs. The whole place was quiet, and there hardly ever seemed to be anyone about. There wasn’t much traffic either. The neighbours were a bit of a curtain-twitching bunch, but I wasn’t going to let that bother me.

One evening, the Savage Twins were just shutting their gate as I parked my car. They stood on the pavement, arm in arm. I thought they were waiting to introduce themselves. I smiled when Keeley said it was their space. They didn’t have a car. She meant it though, I could see that.

She said, ‘Your bit starts there,’ and pointed to an imaginary marker on the road.

I told her I’d remember that in future, and held out my hand.

‘I’m Ruth,’ I said.

They both pushed their free hands deep in their pockets, and Keeley spoke again. ‘We don’t want the fumes coming indoors.’ They walked briskly away, the air filled with curt disapproval. I was left with the image of their faces, the same but different. They both had very high colour, almost purple, with prominent chins, and large, hooked noses. I felt as if I’d been told off by Mr Punch. Two Punches.

It took a while to notice their routine, because they were always so quiet. It took me by surprise whenever they suddenly appeared, coming silently but quickly through the gate, or linked together, sailing up the path like a barge. They were early-risers, always on their way back from somewhere as I opened my bedroom curtains, though I never heard them go out. Their presence looked loud, all that determination and speed; you’d expect to hear stamped feet as they marched along. But they were quiet as shadows. One thing that did give them away was the bottles. Twice a day the Savage Twins would be accompanied by the sound of glass knocking against glass as they brought in, then took out, the bottles.

There was a pattern to it, just like everything else they did. Keeley brought the full bottles home in a carrier bag over her arm, making dull clinking sounds as it banged against her brown coat. That would be in the middle of the morning. Later, the empty bottles would jangle in Rose’s bag as the pair hurried off past empty gardens, out of the cul-de-sac. Their noses seemed more hooked than usual, but that was just my imagination. The only real change was the muttering. By the time they went out with the empties, their headscarves would be bobbing and nodding rapidly at one another in synchronised debate. They didn’t get raucous or reeling drunk, but real hard drinkers never do. They just went a deeper purple, and spat out words as they rushed along. ‘Germs,’ was one I heard a few times.

Once I got the hang of it, I could easily follow their daily pattern. I picked it up during my week off to settle in, and at odd sightings when I happened to be coming and going at the same time as them. Once or twice, I even took up the neighbourhood pastime of peering through the nets, but got worried they’d see my breath misting up the window. I knew what they would be doing even when I was out at work or having a poke around the jumble sales at the weekend.

There was the early morning return from somewhere or other, then they would emerge again and thud off towards the shops. They’d come back with a string bag dangling from Keeley’s wrist, her hand filling the familiar shape of her coat pocket. Those coats could have stood up on their own and still looked like the Savage Twins, their stocky forms moulded in brown tweed. The bottle trip was next, with a long gap before the tinkling return with the empties. After that they would stay indoors for most of the afternoon, making their final outing in the early evening. That’s when they would often be waiting to see if I was parking in their space. As long as I lined up the wing mirror with the gate latch, they seemed happy that my car wasn’t going to fill their flat with fumes. Not that they ever opened their windows. I used to try and forget they were standing there, measuring every inch of road with purple concentration, but it made me uneasy and usually I would end up scraping the tyres on the kerb. Then I’d just catch those big chins clacking, ‘tut tut,’ in harmony, as they hurried away.

Sometimes I missed their return home for the day, but when I did see them, the Savage Twins would have newspapers under their arms. It struck me that perhaps they were quiet because they had no television and spent hours reading. I pictured them going through the papers methodically, Keeley reading out bits and pieces while Rose sat and listened, h

er slightly softer profile scything curves into the air. Again, I felt that twinge of pity for Rose; saw her as the feeble twin, caught in this disciplined timetable existence with her domineering sister. I was making the mistake at that time of seeing them separately.

They were really two halves of the same whole, and if Keeley did all the talking, it was because she was the expressive part. Rose didn’t need to speak while her sister did that for them. They were a unit, with all their characteristics spread across two solid bodies and two ugly faces. It made me think of a puppeteer; one person operating a different personality with each hand. Each puppet displayed its own traits but was forever linked to and influenced by the other. I saw Rose as being overshadowed by her sister.

When they found Rose though, she was talkative enough. Without Keeley there to do it, I suppose she just took over that part herself – almost as if she’d absorbed back into her own character those features which Keeley had been carrying around. If you look at it like that, and I have looked at it an awful lot since I moved away, then the whole remained the same. It all got transferred into Rose, that’s all.

Grave Misgivings

Grave Misgivings