- Home

- Caroline Wood

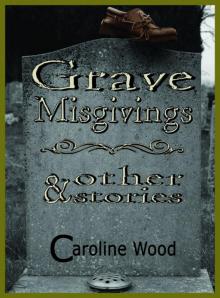

Grave Misgivings Page 4

Grave Misgivings Read online

Page 4

“There was this poor disabled girl …” they'd say. Then go on to tell how they helped me as much as they could. Of course, I have no children of my own. And I still keep myself pretty much to myself, although I can pass easily enough among people and no-one has to know a thing about my other hands. Work is easy enough – it's been a few years since the coffee break performances, and some of those people have left now anyway. It has become a bit like a myth, I suppose – one of those truths that live in the fabric of a building and gets passed on to new staff as they come along. Office gossip comes and goes, but the big things go into this sort of unofficial history book. Like the time one of the directors died in his executive toilet and no-one liked to disturb him for ages, so he was cold and rigid when they finally realised something was wrong and went in, all humble and careful. They found him stuck in the lavatory and had to climb over the top to get the door unlocked. I'm in there with that sort of thing, I think – half real, half invented, depending on who tells the story. But no-one ever says anything to me and I'm the sort that just quietly gets on with my job then goes home without being noticed. They say hello and goodbye and that sort of thing, but I don't get drawn into those little clusters of conversation punctuated by bursts of laughter, or swathed in a conspiratorial hush, and carried out with serious looking faces. Rumours, deaths, love affairs, operations and holidays seem to make up a lot of these talks. But there's no malice towards me now. I’m just part of the office furniture.

What some people will do though, is talk to my shoes. I don't think they even know they're doing it. It’s a bit like when someone has a spot on their nose and you try to avoid looking at it, try to concentrate on other parts of their face otherwise they'll know you’ve seen it – that you know it’s throbbing away like some glowing danger sign. But to make them feel at ease, you just pretend you can't see it. Some people, though, just go ahead – all bold and sharp eyed. They stare so hard at my footwear they could be trying to burn their way through with laser beams and have a proper study of the slim, elegant fingers they've heard all about. When they do finally look up and see my face, you can see they’re surprised. They have forgotten all about me while they’ve been so absorbed by the idea of hands sprouting from the ends of my legs. I can see their imagination having a test drive as they wonder what it would be like. Miles away, they are sometimes, when I startle them back to reality by speaking.

So that's how things have been for a while. I'm trying to find another job; you'll remember that from what I've already told you. I don't behave like that very often – taking advantage of my feet hands, I mean. At least, I didn't until I had the sort of experience that really changes you. Usually I get blurred into the background of life. I am what people call Quiet. It’s been used to describe me more times than I can remember, usually in my presence – as if I'm so quiet that I can't speak for myself. “She's the quiet one,” members of my family say to each other as they run through the ritual of categorisation.

The thing is, I'm not really a quiet sort of person. Not inside. I've learned to stay out of the way, and to be barely noticed – I got my fingers burned you might say, by playing the fool. I’ve kept my head down after that. But there's always been this other side. I get angry, like I did in the interview, and something sort of snaps. Right, I think, now for some bad behaviour. Oh, it's never anything really bad, but this little switch goes off and I stop being the quiet one for a while. It seems to be coming through more often, this other side. And I have to admit I enjoy it, but it isn't what I really want. The satisfaction of tying shoelaces together, swapping handbags and briefcases in meetings, putting notes in coat pockets on buses, or adding the odd mystery purchase to shopping baskets in supermarket queues – none of it lasts long, and the real truth is that I'm lonely. Even more than ever, now.

I don't really know what to do about it because I've got so used to being damped down, being Quiet, that life seems to be settled into a shape I can't change. I've got my family, of course, and when I visit on a Sunday afternoon, they usually have a couple of things for me to do. It makes me feel wanted and part of things.

‘Get that spoon out from behind the fridge, would you love,’ Mum will say.

Or I do a spot of weeding at the back of the border, for Dad, where it would be hard to reach if you had to bend. My sister hates it when I take my shoes off though, always has. I used to sit holding on to the bottom of chairs when I was a child.

‘Put your feet away,’ she'd say, her mouth all puckered like she'd just had her teaspoon of cod liver oil. ‘You look like a budgie sitting on a perch – put them away.’ These days she just makes this tut-tut noise and looks away. I can tell she doesn't approve of my life. She wants me to be like her, married and settled down with a nice house and pot plants. There’s no children yet, but she and Brian have plans. She tells me off for letting Mum and Dad take advantage, says it's not dignified. But I don't mind. I just give her a quick cuddle, and squawk in her ear like Doris, the vicious green budgerigar we had when we were kids.

I want to join in, branch out, let my hair down and all those things they put on the front of glossy magazines. But my hands hold me back. It goes like this – I think to myself that I'll do things, go out more, get involved and meet new people. I imagine myself inviting friends back, having informal get-togethers, that sort of thing. Then I remember my hands and all those embarrassed or uneasy looking faces from the past, and I talk myself out of it. I mean, lets face it, there aren't any glossy magazines for women like me. Features on how to make the most of your natural assets, and advice about nail care never seem to include people with four hands. There are no useful tips on where to get fashionable but well-fitting, hand-fitting shoes. Or, more importantly, how to meet the man of your dreams – and not turn it into a nightmare when he discovers that the hand stroking the back of his knee is actually on the end of a leg.

You see, it's not just a general loneliness – it's that specific hunger for a mate. Soul-mates, they call them in the lonely hearts adverts. I always look just in case there's a man who sounds suitable. There always is, until I get to the bit about what he's looking for in his ideal woman. It's never twenty fingers. Then there’s dating agencies – they'd want to know all sorts of details, but how do you mention something so out of the ordinary. Or do you mention it at all? Isn't it false pretences to keep quiet? I could do what they do in the films, I suppose. Wait for the right moment, then go all serious and say, “There's something I’ve got to tell you …’ The trouble is, it could all be so awkward, and might turn out more like a horror story than a big romance. I really don’t want my most intimate moment with a man to be the ankle episode under that desk.

Don't get me wrong, I keep myself occupied, and I get out and about quite a bit. I go to the cinema, and sometimes to a matinee performance at the local theatre. Occasionally I go out for a drink with my sister while Brian sits half the night beside a cold, black lake with all his fancy fishing gear and a packed supper. I'm a regular at the library every Saturday morning, and I enjoy a browse in the junk shops. I do a lot of walking, all year round, and this time of year, I spend as much time as I can on the beach. I love water, always have. Just being near it soothes me. What I love even more is being in the water. When I'm as sure as I can be that there's no-one near enough to see, I make a quick dash and enter that foaming, swelling, sucking world of constant movement. I'm like a little fish then, my feet hands steadying me like tail fins, and my hand hands pulling me through the water as if I'm on guide ropes. I don't remember learning to swim, though of course I must have been taught. But it feels like something I've always been able to do, and when I'm doing it, I'm not Quiet any more. I come right out of my shell and let the whole experience take me over. I glide and splash and float and dive. Or I just let the sea lull me gently on its surface, quivering all my hands to keep me buoyant, and letting my body mould smoothly over the unbroken waves. I even forget about the mate hunger when I'm in the water. Well, nearly.

Something I can't forget is what happened the last time I was doing my fish impersonation – a little while back when the weather started to really warm up. I must have got carried away more than usual because I hadn't noticed the man swimming, a little bit further out to sea. He was just suddenly there, this head bobbing up and down and arms going over in arches. Good swimmer, I thought to myself. Then I got nervous about how close together we were and started to think about how I was going to get out without being seen and all sorts of things about my hands. He just carried on swimming as if he didn't know I was there. His black hair was so shiny, making his head look like one of those glass fishing floats they sell in gift shops, or have hanging up in nets on pub ceilings. I managed to get back up the beach and put my canvas shoes on while he carried on swimming for a bit longer. When he was back on dry land, he wrapped a big towel round his shoulders and made his way back to his things. As he walked past, he smiled, sort of shyly and nice. And I smiled back, then quickly looked away and pretended I was reading my book. And all the pages got hazy, as if there was only one thing written on them. Hands, don't forget your hands. But I felt warm inside because of his smile, and I made it stay behind my eyelids like after you've looked at a light bulb and it's still there when you look away.

I saw him again as I was going home – sitting right near the edge of the sea, he was, throwing little pebbles into the placid waves as the tide went out. He was dressed this time, but had no shoes on. I noticed how big his feet were. Long and pale. I thought that would be it, thought he’d go back to where he came from and I'd never see him again. I thought he was probably on holiday, or just out for a day at the coast. All sorts of stories about him unfurled in my mind as I cycled home. In the end – I don't know what made me do it – I went back for a walk along the empty beach. I’d had something to eat by then, and the sky was getting thick and clotted with big orangey clouds. The beach wasn’t empty though – the man was still there, walking with his hands in his pockets and his head up looking at the sunset. I was a long way behind him on the open expanse of sand, but I knew it was him, and I followed his footprints not knowing what I'd say if he stopped and saw me, or if I caught up with him.

I felt that warm feeling again, and a buzzing in my head and my tummy. I just wanted to keep on going and I started to lose myself, like when I'm swimming. My canvas shoes made deep dents as I strode along towards the glowing sky and the man with shiny black hair. He had a magnet inside him and I was drawn by it with a smile on my face I didn't remember putting there – it just came all by itself. Then I remembered my hands. That made me grind to a sudden halt and stand on the spot. His footprints led off into the distance, like a line of migrating birds fallen out of the sky. How could I do something like this, with my hands? I had got carried away, been stupid. It was time to go home. Save myself the disappointment. Save him the embarrassment. I don't know what I expected to come of walking behind a man on a beach, but whatever it was didn't fit in with having two pairs of hands.

You might have seen the story, although I think it was only in the local papers. There was a body washed up. Only recent, it was. Had been missing for some time. It was him, it was the man with the shiny hair. Thirty six year old recluse, they called him. There will have to be an inquest and all that but they seemed to be saying he'd drowned himself. Then they went into his life story, like papers do. Secret tragedy of lonely man, it said, and had his mother in quotes saying what a lovely son he’d been and how the family had always tried to tell him he was just as good as anyone else. But he got more and more withdrawn, it said. He'd been born with this rare condition – only a handful of known cases in the whole world, it said. Not life threatening or anything, but in a way it was. For him, it was.

It seems that he’d had this patch of skin with no pigment, or something. It did the usual job skin is meant to do, but it was transparent, completely see-through. Like a jellyfish, I thought when I read that bit in the paper. Only, my eyesight had gone a bit blurred like jelly by then, with these great big tears coming on their own the way the smile did that evening I walked behind him. It can be anywhere on the body apparently, this see-through skin, but his was on his back. A large area, that's how the report put it. I imagined it like a stain spreading across his shoulders and down his spine – a big splash of mercury fallen onto his other skin and blended in. That and the jellyfish image – one of those big, graceful ones that floats on the surface and lets you see all the delicate threads of mauve and blue and purple that keep them alive inside.

Those threads weren't keeping him alive now – not on the inside or the outside. All turned off they were now, like a tangle of electrical cables in a power cut. Still there, still connecting but not conducting – just lifeless. I keep thinking of the way his back looked. I imagine it as an intricate tapestry of colour. Strands as fine as hair weaving in between his pulsing, beating organs – visible like underwater rocks, dark vibrating shapes. And his bones – ivory segments of spine like a line of church candles, the ribs a sculptured cage. The overall effect is a living map, etched in more detail than tattooists could ever achieve. Beautiful – I see it as beautiful. But then it's all very well for me, you might be thinking. I didn't have to live with a transparent back. Didn't have to rush out of the sea (his mother said it was one of his greatest loves; that he went less and less as the depression got a hold on him) and hide myself under a huge towel like some murderer on the television news. Or some monster who would have the holidaymakers screaming and running from the terrible sight they'd seen – hugging their children to their sides for safety and protection. They would call out unkind words, then when they were further away, hurl the ridicule of pantomime and freak shows.

Perhaps he couldn't see the rest of himself. Couldn't put his back behind him, so to speak. Didn't he know about his lovely smile, his fishing float hair, his long pale feet, and the magnet inside him, pulling me along the beach that evening? When I remember that now, I picture myself reaching him. We don't speak. We don’t say a word. He just looks at me and then he takes his tee shirt off, slowly and with this air of sadness and resignation. It's as if he knows what's coming. But he doesn't, that's what tortures me in this daydream. He doesn't know because he hasn't made allowances for my side of things. And I've already told you my side. I think his back is beautiful – I think he is beautiful.

So in my repeated version of events, when I go over and over that walk in his footsteps, he takes off his pale blue tee shirt and turns away from me. He is showing me what words could never prepare me for. I stare silently into him. Before he can bend to pick up his top, I lift my hand and trace very lightly with my finger down the centre of his back. It feels warm and firm, but looks like my hand is walking on water. That's how I imagine it, anyway. Same as I imagine hearing him make this little sighing noise as he leans just a tiny bit back towards me. But instead, he took deep gulps of sea, filled up his spongy, undulating lungs and gave in to the currents and tides.

That's part of my bad behaviour, what happened with that shiny-haired man. I get these knots of feeling that I can't undo, even with all my fingers. Sometimes one feeling comes out on top of the others, but mostly they are all mixed up together – the rage and the guilt and the sadness, and that waking up to realise it all over again in the morning. For a few seconds everything seems normal. I lie there like I always did, listening to the day start, watching the light get stronger. Then it flashes back at me like headlines hanging in the air above my bed. And I'm filled with it all again – the real bits, the dream bits, and the if-only bits. I shout at him sometimes. When I do the walk we did together – the one he didn't know about. I do it a lot now, and I shout at him that he should have let someone tell him how beautiful he was. What I mean is that he should have let me tell him. What I really mean though, when I shout into the fading light, is that I could have made a difference. I'm shouting at myself, you see. For being so tied up with my hands and everything. For stopping before I got to

the end of the footprints. For not following his shining hair and shy smile. What I sometimes do as well, when I’ve walked on his invisible footprints – I sometimes take my shoes off and paddle in the sea. My hands waving at jelly fish as they sway gracefully in the water.

* Growing Things *

One of the constants in my life was Cobb. He was always there and he never changed – reliable, dependable Cobb. He was the safety net under the shaky tightrope-walk of my young life. My Mother and Father did try to make time for me between all their business commitments, meetings and social engagements but they were extremely busy people, and always had too much to do. I was always good at occupying myself, and would spend hours creating vibrant internal worlds. Then I’d escape from the creaking loneliness of the large, empty house. The attic was one of my favourite winter places. Nobody came to look for me as I dwelled there among imaginary people and pretend events. The garden was my favourite place of all though.

All summer long, I'd be in the garden from early morning until the moon glowed. Cobb was always there, and he let me help him, taught me about gardening, and showed me how to make things grow. He had time for me; I wasn't a nuisance to him, or an afterthought – like with my father, when he gave me his slightly puzzled look as he rushed through the gate. Seeing me, I used to think, was a jolt to him, like he’d just been reminded he’d got a son. And I could see him frown before he drove away, perhaps promising himself that he would give time to this overlooked project as soon as he’d got a space in his crowded diary. Or maybe he was deciding to pass the duty over to my equally busy mother, who had people to see all the time. She used to give me gifts and ruffle my hair as she grabbed her car keys from the hall table, leaving a trail of pungent scent behind her. That smell used to make me sneeze.

Grave Misgivings

Grave Misgivings